Before you take off – the frontside punt

December 14th, 2011

THE FRONTSIDE PUNT

The Approach

Spying a perfect little launch section, approach with heaps of speed, and as you begin to move up the ramp shift most of your weight to your back foot, using your front foot to simply guide you up to the top of the wave. Maintain eye contact on the section you’re hoping to boost from. Drive through your bottom turn into a clean launch off the top and carry your momentum off the lip into the air. Your board needs to lay flat on the lip when you take off. The key here is to get up high. “To do that you need to drive your momentum off the top of the wave by pushing off the tail of your board,” explains Taj Burrow.

The Moment

Once you hit the section try to completely un-weight your board by springing above the lip. Continue to keep the weight off your board during the altitude climb, and at this point think about contracting your upper body towards your lower body – this will make you more compact and centered as you fly through the air. “As you get airborne, try and turn the nose of your board towards the beach by straightening out your back leg. Just stay above your board, and pull your knees up to your chest to stay in control and to stay stylish in the air. The wind coming towards you can really make a difference here,” continues Taj. “You’ve got to stay over the top of your board, and not lean back too far.” Consider applying a little pressure with your back foot to ensure that your flight path is spot on. If you feel like your board is going to get away from you, this is the time to grab the rail. There are all kinds of different variations you can do – double grabs, mute grabs and frontside grabs; almost anything you want. I don’t really plan it all out most the time. I just experiment and learn by feel.” As you reach the apex of the air you’re going to need to spot a landing zone. Staying focused on where you’re coming down is the key to sticking it.

The Recovery

The toughest part of flying is undoubtedly the landing, so make sure you’ve got yourself together as you start coming down. Be it a busted knee or a tweaked ankle, it’s really easy to get hurt landing airs, so don’t be afraid to bail out if you don’t feel right. If you do feel good, start coming down with weight evenly distributed and maybe just a bit more pressure on your back foot. “As I start to come back down I let go of my grab and check out the softest landing area, which is usually the whitewater,” tells Taj. “I try to extend my legs a little so my knees can absorb the impact.” Avoid the temptation to ‘stomp’ the move down because straight-legging it at this stage is a recipe for disaster. Negotiate the whitewash by quickly squaring up your shoulders over your board, and with knees bent and tucked firmly under your torso. From there it’s just a matter of not falling off.

Add Some Style

Parko adds: “Style is a lot more important today. It used to be guys would just throw it up into the air and let it fall where they may. But guys like Taj have made style an issue by doing it so well. There are two ways to add style, says Parko. First, use your knees as shock absorbers, and stay low to keep your center gravity and balance. And second, finish strong with more speed: connect as smoothly as possible, complete the wave, and continue to ride.”

This post was taken from Surfing The Manual: Advanced by Jim Kempton.

A barrel of fun – frontside tube riding distilled

December 9th, 2011

Peter Townend, the 1976 World Champ, likes to tell the story of Gerry Lopez giving him the secret of riding the tube: “I was a grommet at Coolangatta, surfing Kirra, and I could get into the barrel, but I couldn’t get out,” relates PT. “So Lopez showed up on the Gold Coast with Jeff Hakman and Jack McCoy.

Being the brazen little grom that I was, I walked straight up to him and introduced myself. I told him I’d been surfing Kirra and he was interested in going to try the tubes there. So I straight-up told him that I was having trouble getting out of the tube. ‘Let me tell you a little secret’, Lopez confided. ‘You see that big water pipe over there? The next time you’re in the tube and you are having trouble, take your front hand and point it directly in the center of the cylinder.’ I went back to Kirra that very next day, and every time I put my hand in the eye of the cylinder I started making it out of the tube!

It’ a simple tip, but I never forgot it.” The history of tube riding is a storied affair primarily built around the training ground of Banzai Pipeline, where nearly all surfing’s early barrel techniques were developed beginning with Butch Van Artdalen’s initial encounters in 1962, earning him the first title of Mr. Pipeline.

Jock Sutherland was next in a succession of regal pipe masters that was most epitomized in the early 70s by the zen-like grace of stylist Gerry Lopez. The torch was passed to Shaun Tomson in the winter of 1976, when new equipment and new vision allowed Tomson to actually begin maneuvering inside the tube at Backdoor.

The Pipeline Masters contest created a forum for performance that has crowned a number of heirs to the throne, including multi-time winners, Rory Russell, Larry Blair, Derek Ho, Tom Carroll, Kelly Slater and Andy Irons. For aspiring experts there’s no other place so sought after, and dreamed about than the tube. To ride in the barrel requires commitment, skill, and the ability to read the waves in instant detail. The punishment for errors is severe; the prize is communion with the very essence of the sport of surfing. It is estimated that only one in twenty surfers can confidently negotiate the tube. Here are some takes by the world’s best, to give an edge to the upcoming 5%.

1. SPEED

Surviving the barrel is all about speed; how to get it, and how to control it. To get deep in a barrel, you need to decelerate, but to get out, you need as much speed as you can get. Learning how to decelerate and accelerate will give you control of your tube ride and therefore allow you to get as deep as you can, and still get out.

2. SHOULDER IN

“The best trick I can remind tube riders to remember is to keep your lead shoulder in. It completely changes the body positioning. At this point you can make adjustments in the tube. The key is to make the negotiation between not getting too high (so that you get sucked up the face and over) and not getting too low (so that you lose your speed or get caught by the falling lip.) Both Mick Fanning and Joel Parkinson have developed a new approach which puts their weight on the front foot almost exclusively. Their back foot is turned over – the heel is rarely touching the deck. They put all their weight on the front foot and with today’s boards, the speed is built around weighting and unweighting.” Shaun Tomson, World Champion.

3. SETTING UP

Another important aspect is setting up the turn to position for the tube: Sometimes a hollow section will be coming a ways down the line and you will want to make a couple of quick pumps to position yourself right where you want to be as the lip pitches. If the tube comes up quickly, sometimes it is necessary to make a quick hook turn on the face, get your rail in, and duck quickly under the lip.

STEP BY STEP

1. TAKE-OFF

Barreling waves are steep waves. Barreling waves are fast waves. Therefore, paddle fast, and at an angle. You must take off right on the peak, dropping down the face. Depending on how fast the wave is, you need to decide where to bottom turn. On fast waves like Pipe, you’ll drop to the bottom with no chance of engaging a fin. You must get the fin in as soon as possible.

2. BOTTOM TURN

This step is crucial. Too late and you’ll lose speed or find yourself outside the curtain. Too soon and you out-run the lip and have to stall to get back in. When you start your bottom turn, keep the knees bent like a coiled spring, and point your head in the direction you want to go next (back up the face). In small waves, now is the moment to make yourself small, to avoid decapitation.

3. PULLING IN

This is the moment of truth, when you must get yourself into the right part of the wave. You need to be half way between the top and the bottom of the wave. Too high and you get your neck chopped by the lip. Too low and you will be drilled. Use your back foot toes to engage the fin for more height. Release the toes and weight the front foot to drop back down the face. The key success factor for this: keep the high line as long as possible; height = speed, and speed = a safe exit.

4. SPEED

Surviving the barrel is all about speed; how to get it, and how to control it. To get deep in a barrel, you need to decelerate, but to get out, you need as much speed as you can get! Learning how to decelerate and accelerate will give you control of your tube ride and therefore allow you to get as deep as you can, and still get out the end.

5. DECELERATION

To get deeper, decelerate. Hand-dragging is the most effective way to lose speed when there is little room for maneuver. Stick your back hand into the wave… Not too sharply or you are gone! Weight shifting is the cleanest but slowest way to lose speed. Rock back onto your back foot. This brings the nose up and de planes the board, creating drag. Some small s-turns or wiggling; will slow your progress and allow the lip to catch up. This is hard to do in small tubes where you are crouched over the board.

6.THE RIDE

Staying with the lip is all about control. Accelerate and decelerate to keep you in the slot, using the techniques in step 5. Hold your line no matter what.

7. EXIT STRATEGY

You need to use all that speed you banked earlier and enough height to allow a sharp acceleration. Here are some tips on how to get the speed you need to exit:

Put weight on the front foot to reduce drag.

Rock back and forth while applying, and releasing, back-toe pressure. This engages then releases the fins and literally “squeezes” speed out of the board.

Keep low and tight; loose arms and heads create drag, and add to the risk of lip chop.

If you look at the exit, you will go through the exit! If you look at the roof, you will go through the roof. If you look at the board, you will drop too low.

This post was taken from Surfing The Manual: Advanced by Jim Kempton.

Scrubs – five tips to scrubbing a jump with a sam hill

December 5th, 2011

A modified whip and a recent addition to all top riders’ jumping arsenal is the scrub. Following on from the trademark trick of motocross legend James ‘Bubba’ Stewart, the scrub is all about being able to hit jumps flat out without catching much air by absorbing the kick.

Get these nailed and you’ll be able to hit any lip full throttle without losing any speed.

FIVE TIPS TO SCRUBBING A JUMP WITH SAM HILL

1. Approach the lip as fast as you feel comfortable.

2. Set yourself up in the middle of the bike ready for take-off.

3. Lean the bike slightly to one side as you are heading up the crest. This will take a lot of commitment.

4. When your front wheel is at the top of the crest, turn the handlebars down to the same side your bike was slightly leaned to and flatten the bike underneath you. The lean in the air should be an extension of the turn you started on the ground.

5. Straighten the bike up for landing using your arms and legs and stay focused on the next section of the track.

This post was taken from: Mountain Biking The Manual by Chris Ball

Spot of the Week: Banzai Pipeline, Hawaii

December 1st, 2011

It’s one of surfing’s longest running traditions that the final (and often world title-deciding) round of the ASP world tour is held at the awe-inspiring Pipeline. This year the final round of the Triple Crown series, the Billabong Pipe Masters takes place during the waiting period from 8th to 20th December.

In the run up to the event we take a look at the famous wave:

At the Southern end of Ehukai Beach Park. Going North from Waimea about 2 miles, small alley on left before Sunset Beach Elementary.

Pipeline; Probably the squarest barrel on earth. ..when it’s on. Pipe needs trades, and the right swell (W to NW at 4 – 25ft) to work properly.

Take one of these away and you can have a shapeless, punishing mess. The rule of thumb is; the more west the swell, the heavier and hollower the wave.

Pipeline is a series of 3 reefs working from the inside to the outside as the swell increases. First Reef: At 4 ft, you can have the

most perfect barrels followed by a short whack-able section here. The crowds at this size will frustrate, and the dropping in is blatant.

The wave is so close to the beach that spectators can get closer to the action than any other surf spot. At 6-8ft, the peak appears close to dry

sucking off the reef, and the drop is a free-fall. A mistake could see you jammed into a crack in the lava reef, but successful riders will make the

bottom turn, and stand tall in a super-wide almond shaped barrel. Then it’s a speed-race out onto the shoulder, which eventually tapers into a sandy channel.

Second Reef: From 10 or 12 ft plus, another crop of lava pushes up bombs another 100 yards out to sea. These can be mountainous

jacking peaks which reform on first reef giving 2 rides in 1. Take-offs here are more critical than any wave anywhere. Timing, commitment

and a heavy board are essential to manoeuvre into the elusive time-space window between being pushed over the back by the gusty winds

funneling up the face, and too-late drops straight to the bottom. The entire length of the wave is a full-power situation, with the lip ready to cut a surfer

down at any moment, and even the latter half of the ride can produce truck-sized barrels.

There’s anoccasional 3rd reef too, for monsters up to a much contested 30 feet. Now a tow-in domain, and quite rare to see it perfect.

Paddle-out fast, West of Backdoor. Current will sweep you East of the peak into the channel. Crowds to the extreme. Drop-ins are

the rule not the exception. Frustrated caged battery-chicken surfing. Experts only.

Backdoor: The right off the same peak as first reef, is an equally if not more heavy tube machine, with even more shallow reef and

rocks to contend with. Backdoor tubes often end in shut-down or dry-suck, and the successful surfer will make speed his friend. No

time for turns here. Works on similar swells, although likes more North than Pipe itself. Too much West in the swell, or too much

size, and it will be a dangerous close-out. From 3 to 10 ft. Crowded to the extreme. Drop-ins from body-boarders and surfers better than you.

Shallow reef with deep cracks to get stuck in. Current. Thick guillotine lips.Both these waves have claimed lives, and may be best experienced

vicariously. Try to catch them early or late season or you may not get a single wave. If you want expert tuition to help get your confidence up

(or are prepared to admit that you need some lessons), The Hawaii Surf School is based on the North Shore, on 808 638 7845. Beccy Benson and

her team of pros will hone your skills whatever your level.

Hitting the lip – this is the most essential part by miles

November 27th, 2011

Getting it right while you’re still on the ground will make the airtime part easy. Although you may be thinking about the jump as the take-off and landing, add the few metres before the transition into your thoughts. You need to be planning and setting up a few bike lengths before the lip so that when you get there, everything is done already. One of the hardest things to master is learning the concept that, the less you do, the easier it’ll become.

Stick on your favourite film and watch any top rider; you’ll see that they rarely yank on the bars and spring off the lip like a gazelle having a seizure. Instead, the transition from dirt to air is seamless. The line and arc should begin on the take-off and carry on through the

air and onto the downslope.

On the run-in, spot your take-off point. That should usually be the highest part of the jump. You need to try and make sure both tyres reach this point of the jump before they lift off. Hopping off the transition too early will only cut short your airtime and bring you down heavily with no flow. By keeping an eye on this point, it should be easier for you to gauge your speed and get the timing of all your movements’ right.

THE PUMP

Hand over as much work as you can to the trail. The more you can get from the dirt, the less you need to do yourself. Pump the compression before the jump starts to rise. If you’re coming in fast, you might not have to do too much, but if you’re rolling in slow, exaggerating the pump with your arms and legs will add height and distance to your jump. The pump can also add stability to your riding. The more planted you are on the ground, the more confidence and balance you’ll have so don’t let yourself get all light and off-kilter before you even get to the lip. As with most general trail riding, the bike is better stuck to the ground than it is skipping over the top.

SPEED

The pace you hit the jump at can be tough to gauge to begin with. Start slow and build up on tabletops, where the consequences of coming up short aren’t as severe as a double. The more jumps you hit, the more you’ll understand what’s going to be needed to get you the distance. Technique can also play a part. The more proficiently you pump, the slower you’ll be able to go and still clear the gap. If you can only reach the downslope of a small jump by frantically pedalling at the take-off then something’s amiss. Go back to the basics and refine your flow, balance and pump.

LIFT OFF

Now that you’re approaching with the right speed and you’re solid and in balance, you can start to work more on the take-off. Pumping should have moved you slightly down and forwards to load the bike – like coiling a spring. Now you need to release that pent-up energy by following it up with a gradual move backwards. The lower you move from, the more balance you’ll have so recruit your hips into doing most of the work. Keep in mind that unlike a manual, where you do all the work, most of the effort will come from the physics of that spring, so keep all body movements very subtle.

If you were to roll your bike at the lip without you on it, it would take off on its own so all you have to do is make sure you’re not loading the front wheel. All it’s wanting to do is take off – so just let it. As the 19th century proverb says, less is more.

BACK UP

The rear end needs to mirror what the front has done only hundredths of a second earlier. As the lip is the take-off point, keep your weight off the front until your back wheel has rolled up the transition and is now at the same spot. This can seem difficult, but in actual fact it’s pretty simple. Just like you took your weight off the front by moving backwards, you should now take your mass off the back end by moving forwards again. Too much and you’ll either start a front flip or nose dive into the landing, too little and your rear tyre will stay planted on terra firma. It’s a fine balance, influenced more by your timing than by how much you’re moving. Subtlety is key, so keep the movements minute.

AIRTIME

If you’ve done all your jumping using the lip and the trail that precedes it then this part will be effortless – just like in those movies. It’s the hang-time you’re now experiencing where you can spot your landing or start trying tricks. If you feel like you’re holding the bike in the air, chances are you’ve gone for the old faithful yank on the bars and need to re-think your take-off. The pedals you’re using shouldn’t make a difference at this point. With the weight shift back and forwards, the bike wants to take off underneath you and will be following the path you set it on at the start. If the bike is dropping away from you, it’s back to the drawing board and time to re-master your take-off. Don’t take the easy option and fit a set of clipless pedals, they’ll only restrict you later on.

POP

We’re not talking Britney Spears here. The pop you get from the lip is the result of a number of things. As McCaul says, “You might have to bunny-hop more off the lip if you need more height than it’s going to give you.” In this sense, exaggerating the boost you’re going to get from the jump will require you to do a bit more work. It’s not worth trying this until you’ve got mellow, relaxed jumping dialled as the timings and techniques are a little more complex. Initiate the entire movement from the pump and use this compression as the trigger for all your other techniques to follow on from. On the approach get stable and central with your pedals level, push hard into the compression with your whole body weight and as you take off carry out the same moves as before but with extra effort and power.

The bunny-hop can be introduced nearer the lip to squeeze that little extra from the height but make sure you’re still using as much of the transition as possible. Try and let your moves be dictated by the shape of the ground rather than just pulling a monster bunny-hop off the top. It won’t get you that far and will win you zero style points at the same time.

This post was taken from: Mountain Biking The Manual by Chris Ball

Backhand across the face – A successful backside attack begins with your bottom turn

November 25th, 2011

Your ability on your backhand begins and ends with the proficiency of your bottom turn. And while, in terms of projection and speed, the basic physics behind a backside bottom turn are relatively similar to a frontside bottom turn, it’s the mechanics that are completely different. Frontside bottom turns are considerably less technical for the simple fact that when you commit to the turn, you’re facing the wave.

There’s much more of an unknown factor when you’re setting things up on your backhand, and there’s no better place in the world to study this than Pipeline. Watch the best frontside surfers there, and you’ll notice that they practically fall into the pit, waiting for the ocean to throw over them before setting their rail.

There are very few long, drawn-out turns. But backside surfers don’t have this luxury; they have to rely on experience, instinct and one hell of a bottom turn. Either one of the Irons brothers serve as a perfect example. Bruce Irons stays low over his board, grabs his rail, sort of sideslips under the hook and about halfway down the face engages his inside rail and fins. This sets him up for the tube almost immediately, which allows him to sit far back on the foam ball from the beginning to end of his ride.

On the other hand, Andy Irons will often drop straight down the face, and as he starts to get to the bottom of the wave really leans into the turn, and depending on the situation, he either projects out of the turn and down the line, or picks a more straight-up path into the pocket.

Considering Bruce and Andy are both Pipe Masters, either approach is more than suitable. But before you go hucking yourself over the ledge at Pipe, you’d better understand the fundamentals first. Here are a few ideas to get you thinking:

The Approach

As with every other maneuver in surfing, a good backside bottom turn starts with your ability to successfully make the drop. Of course, there are exceptions. On particularly fast, racy waves, you’re going to want to angle across the face, so as to not get stuck behind the section. But if you’ve got some open room to roam, you should try and stay as straight and close to the power zone as possible.

The Turn

Start your bottom turn the instant you reach the flats and at the point of maximum speed on your drop. “Get low and lead off your front foot,” says Mark Occhilupo. To begin your bottom turn keep your knees bent, lean on your heelside edge, and turn your upper body in, looking over your front shoulder. This will initiate the turn and allow you to see the lip in front of you. It’s here that you’ll be able to decide whether you want to crush the lip or drive down the line. Your weight should be evenly distributed between your front and back feet. Ride through the beginning of the turn without dragging your heels in the water in order to maximize your speed. It is very important to keep your original line through the turn so you don’t lose any speed. Try to pick the right line from the beginning, maintaining one long, flowing arc. If you’re really pushing the turn it should be almost like you’re sitting in a chair, your butt just a few inches off the water’s surface.

The Next Step

When you begin to go back up the wave, transfer most of your weight to your back foot, and drive up the wave face to gain the maximum amount of speed possible for the wave. “My back hand will just touch the rail on the upward swing,” says Occhilupo. “Focus on the section of the lip you want to hit, and on pushing with your back leg.”

The Details

Just like the frontside bottom turn, paying attention to the details is the most important thing. “An immediate transfer of weight is the secret,” says Occy. “With the right track, the correct punch off the bottom and the right angle of rail, you should be generating the speed and positioning you need for your next move. From here you’re off and running.”

This post was taken from Surfing The Manual: Advanced by Jim Kempton.

How to handle rocks

November 21st, 2011

Whether it’s the barren, wind blasted moraines of the high Alps, the huge glacial formations of Canada or the boulder strewn trails at British trail centres, handling rock sections well is essential for success. From sliding down loose scree slopes with fist sized rocks moving underneath your tyres to traversing off camber granite rocks the size of a house, a certain mentality is required.

It takes confidence and calm determination to conquer the section rather than becoming its victim. The rocks will always win in a contest of hardness, so absorption is the way to go. Keep yourself focused on the end goal and let your ego have a small knock once in a while. Better that your mind takes the hits than your head.

The 2002 UCI Downhill World Cup in Fort William was a moment in time where sheer rider strength and brutality conquered all that lay before them. Chris Kovarik won by 14.02 seconds, one of the biggest margins in modern pro men’s finals history, yet it wasn’t just the gap he won by that was impressive. To go that fast, Kovarik had to take on a course that had been torn apart by the wind and rain all week. He came across mud covered hard Scottish rock on almost every section of the track yet pushed on, took each hit and destroyed the field.

STRENGTH

As one of the more powerful riders, Kovarik puts his strength at the top of the list. “I can make the bike stay on line by holding on and keeping it straight through the rocks”. By staying solid and not getting knocked off his line, Chris can keep it between the tapes and take hit after hit. Although gruelling, it’s this ability to take the rocks on at their own game that gives him the edge he needs to win.

Not only do you need to make your upper body strong enough to keep the bike on track, you also need the endurance to take the endless hits that a rocky run will throw at you. In Kovarik’s opinion, “You need to make your muscles more efficient to hold on well. Get down the gym and develop your core. You don’t just need bulk, you need the efficiency and stability that comes with it”.

BRAKES

How you brake will depend on what the surface is like. If it’s wet and the rocks are slippy, you need to go steady and approach the braking just like you would on a rooty section. As grip only comes when your braking is either light or completely non-existent, go easy on the anchors. No panic braking, and be prepared for a bit of movement under the wheels.

If the slope is steep and rocks are loose you’ll need more bias on the back brake to stop the front end from pushing off the trail. A bit of a rear wheel skid here or there is no problem, in fact sometimes it can really help to control the bike and keep everything on the straight and narrow. Plan your braking for what lies ahead. If you’re cresting at mach 9 into a rock garden you should be thinking of taking some speed off early. Once you hit the rocks, forward momentum and letting the wheels roll will be a huge help.

SET-UP

For a rocky ride, do a few things to set yourself up properly. To prepare for his ride at Fort William Chris Kovarik had this to say. “Suspension set up is super importan. If your bike is set-up too soft you will be falling into all the holes and hanging up on every rock. If it’s too hard you will be bouncing off line and getting beaten up.

You don’t want to be pinch flatting every run in those rocks so pay attention to tyre pressure and experiment with it. With your brake levers, try to adjust them as far in as possible without them crushing your fingers on the bars. Don’t have your braking finger struggling way off by itself. Grip it closer to the bars with the others like a fist. This should give you way better strength to hold on with”.

This post was taken from: Mountain Biking The Manual by Chris Ball

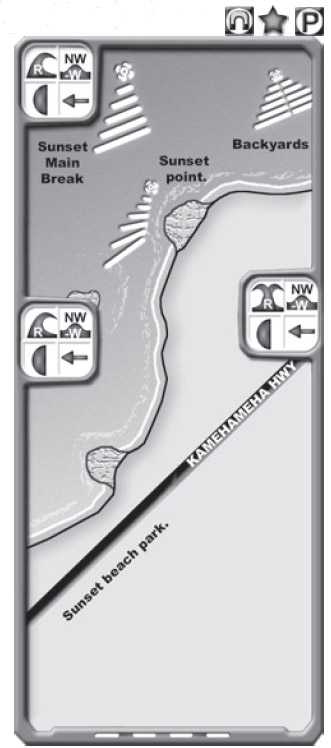

Spot of the week: Sunset Beach, Hawaii

November 17th, 2011

Next week the Van’s World Cup of Surfing will be taking place at Sunset Beach, Oahu, Hawaii.

Before the event we take a look at one of the longest beaches in Oahu.

Up the Kam Hwy till you see the parking spaces on the left after Kammies. Sunset; Set of reefs dealing with

swells from N through W. Northerly swells break the wave up into different peaks, and make the place a little more

sharing as a result.

On a classic big West swell with trades, Sunset is a heavy, jacking peak that develops into a hollow, sucky, thick lipped beast.

These swells catch the trades side-offshore, and the result means heavy long boards and serious intent are required to get you

into the wave. 4-15ft. Major Rips. Crowds. Expert.

Sunset Point, further inside, is a quality R breaking at 3-6ft on NW – W swells. It can lose shape on N swells. Crowds. Intermediate.

Just East is Backyards; fickle, often shifty proposition that goes left and right, and works from 4 to 1212 ft. Currents and unpredictable

peaks absorb surfers well. Expert or tow-in.

Finally, Outside Sunset: Huge right tow-in spot when Sunset is closed out. Can work all the way through Outside Backyards, which is a

right / left outer monster too, with shallow reef under the end section. Hell-men only!

Frontside signature the cutback: putting your own stamp on a timeless maneuver.

November 11th, 2011

A fraction of a second captured by Tom Servais on the North Shore during the winter of 1992 set a new standard for commitment in the area of radical rail transitions, which had not been exceeded since the Michael Peterson era of the mid-’70s. For the thousands who held Tom Curren in the highest regard, that moment provided explicit evidence of his grace, style and power in the water.

The iconic image of Curren’s grab-rail front at Backdoor helped to shape the approach of an entire generation, and still stands as possibly one of the single greatest frames ever photographed in our sport. While one of the most essential maneuvers in a surfer’s repertoire, the frontside cutback is not only functional, but also provides a rare opportunity to add your own signature.

From Curren’s fundamentally flawless carve, to Joel Parkinson’s sweeping lines, to Andy Irons’ aggressive power turns, from Donavon’s come-from-behind arcs, to Rasta’s soulier-than-thou body English, all turns serve essentially the same purpose, all the pageantry is just a matter of aesthetic appeal. The difference between a cutback and other reversals of direction (like snaps and laybacks) is that the maneuver is done at continuous fluid speed.

The cutback allows you to use the rail of your board, and brings you back to the source of the wave where you can generate more speed for your next hit. Like a fingerprint, no two surfers’ cutbacks are the same, but there are some universal things that make for a great frontside carve.

DALE VELZY

One of surfing greatest innovative shapers and entrepreneurs, explaining the evolution of early modern surfboard design, referring to Bob Simmons who first used light balsa and foam for surfboards.

Simmons knew how to make ’em light. But I knew how to make ’em turn.

Six fundamentals of A good cutback

1. TIMING IS EVERYTHING

Don’t make your turn too early when the wave is too vertical, but conversely, don’t glide too far out on the face where the wave is too flat. Keep your eyes focused on the part of the wave you want to hit. It is best to hit the section where the lip is just beginning to break at the edge of the whitewater.

2. GO TOE-TO-HEEL

Start bending your knees when you come up the middle of the wave face, and shift your weight from your toeside rail to your heelside rail to initiate the cutback. As you lift out of your bottom turn, keep your board flat on the wave face to retain full speed, then un-weight your front foot and lean slightly back.

3. THINK RAIL-TO-RAIL

As your feet and weight shift from toe to heel, the outside rail rolls over and begins to engage the wave. The more speed, the easier the transition from inside rail to outside rail. But as you transition, your mind needs to make the change too.

4. KEEP YOUR MOMENTUM

Be sure to watch your board’s nose as you reverse direction, because you want it to fit into the wave shape to maximize speed. As your board turns back towards the breaking wave, keep the fluid momentum going. Don’t let up midway through the turn, which is tempting to do when you want to keep going down the line. This lack of follow through will make you lose speed, the all-important aspect to making your next move. Bend your knees and keep driving through what is now a backside bottom turn.

5. FINISH STRONG

Your board should finish with the nose pointing straight back towards the breaking wave, ready for another drop with maximum speed. Just as in your initial take-off, look down the line when you have finished the turn, read the wave to determine angle and steepness of the drop-in. The big advantage you have at this stage, is that you are already on your feet and having maintained speed through both your first moves, are much more ready to position yourself to go straight into your next bottom turn.

6. NEXT MOVE OPTIONS

At this point there are several approaches to the next move, and they will depend on the shape, size and power of the wave.

6.1. AIM HIGH FOR THE LIP – Aim high for the lip and essentially turn your cutback into a re-entry. Occy says this gives you the best opportunity to get down the line if the wave is hollow and powerful. It also forces you to come down with the lip.

6.2. AIM FOR THE MID SECTION – Aim for the mid-section with a classic roundhouse cutback and catch the oncoming whitewater with power. Joel Parkinson says what he loves about this line of attack is holding your turn as long as possible for maximum carve factor. It generates the most momentum, he says, but requires taking the brunt of the wave’s power and can sometimes be risky in big surf.

6.3. AIM LOW – Aim low and attempt to avoid the wave’s power and avoid being knocked down by the swirling foam. This may be the safest route in bigger surf, but it does offer the best chance of losing the face of the wave and being left in the whitewater. The best way to avoid this is to take the steepest route down the face and to do a sweeping bottom turn off the flats, initiated by a drop just like the one you did on the take-off. Now you are putting moves together.

This post was taken from Surfing The Manual: Advanced by Jim Kempton.

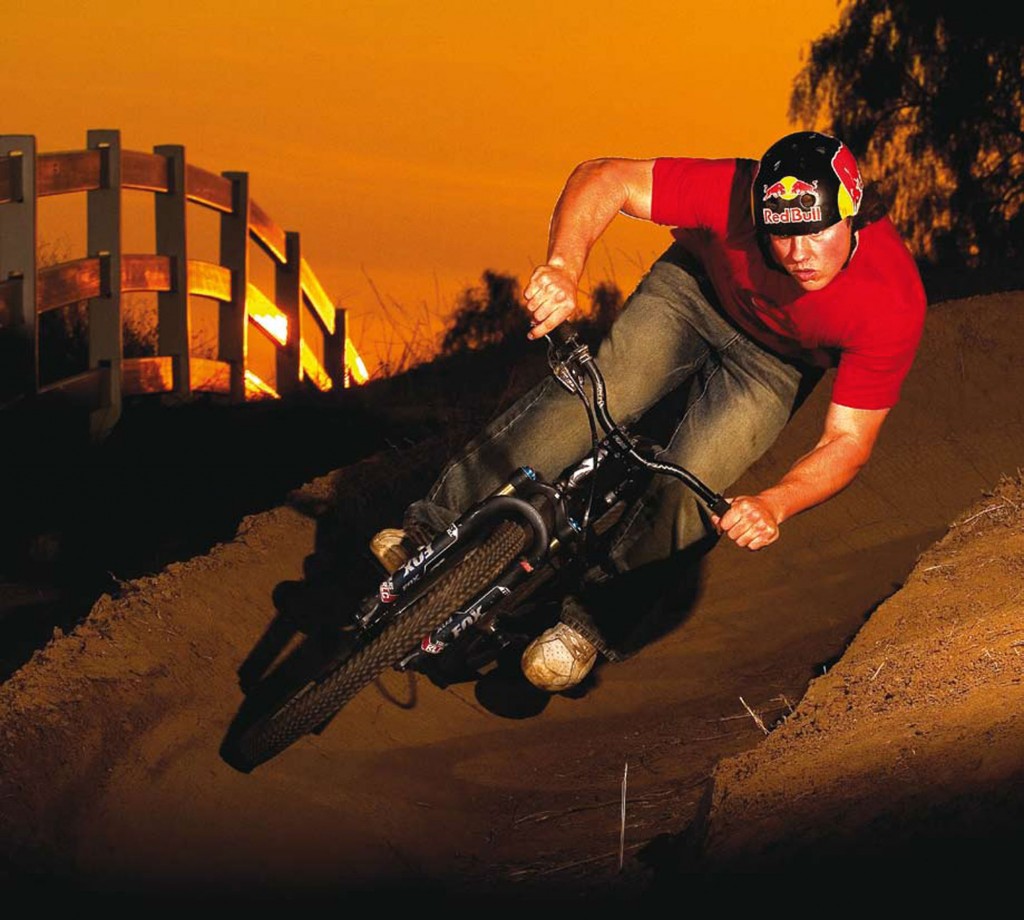

Berms- berms are everywhere

November 9th, 2011

From the manicured perfection of the Beijing Olympic BMX track to the upper slopes of the Fort William UCI World Cup course, the abundance of berms now means that nailing them is an essential skill.

Think of a berm as an old friend. Rarely do they cause you grief; in fact their very presence should mellow you out. Hit them right, and they can add a whole new dimension of flow to your riding.

A well-sculpted berm will allow you to change direction effortlessly and give you a bit of speed too. The flip side is that if you’re unsure of how to ride the

steep sided bank, a berm can look pretty intimidating, as it rears out of the trail ahead.

GO WITH THE FLOW

The best thing to do with a long shallow berm is to let it do the work for you. If the shape is right, the line should feel natural as the gradient holds you in place the full way around the turn. If the berm is big and open enough for you to be able to choose where to go, try and follow the idea that the steeper it is the faster you can go. So, as berms tend to steepen as they rise, a slow pace may mean that you stick to the bottom whereas, flat out, you should be looking to stick to the steeper lip near the top. Even as you hit tighter and steeper berms, you should feel like the dirt is doing all the work.

Aim to make the corner as smooth as possible. If the berm tightens towards the end, adjust your line with it. Likewise if the corner opens up, you should be easing your line out to reflect that. The more consistent your line, the more stability you’ll get and it’ll be easier to start introducing more speed.

BRAKELESS

Brakes and berms don’t really go together. In fact, the very presence of a berm should relax you and make you feel like you can keep your speed rather than having to slow down. To help with your confidence think of a berm as something positive rather than another trail obstruction. This mindset should stand you in good stead to railing the turn with prowess and skill.

The first thing that’ll happen if you pull on the brakes mid-berm is a sudden change of line. As you’re trying to get your tyres perpendicular with the dirt, any braking force will start to pull you upright making the corner a struggle to get around. Like a flat corner, if you do need to scrub some speed, do it on the way in, while everything is still upright and there’s plenty of grip available.

When you get into the berm, look for the exit. There’s not much else you need to be thinking about. The further you can look around the berm, the more you will carry your speed. Once you are comfortable with the idea that the berm is your friend it will all become easier and you’ll be able to relax and think of what to do next. Thinking a few steps ahead of yourself is the way to ride if you want to get really fast.

FRONT LOADER

With the bank there to support you, it’s possible to put more weight on the front wheel than you could on less stable terrain. As you come into the berm, start putting more force through your arms, as if you’re trying to push the front tyre into the dirt. The steeper the bank you’re pushing against, the more weight you should be able to trust the front tyre with. It should all happen nice and slowly. Remember that flow we spoke about. Riding your bike is a combination of lots of different moves happening together so always let the trail, the grip and your feeling dictate how much you’re going to move. Load the front gently and progressively rather than all at once. It’s only once you start riding like this will you truly be able to notice the difference between suspension settings and contrasting tyre treads.

ATTACK, ATTACK, ATTACK

As you get more confident with hitting berms without hitting the brakes, you can start pumping them for speed. It’s incredible how much speed you can get from a berm and just how aggressively you can hit them. Ever seen the images of riders doing a power-wheelie out of a tight berm after hitting them so hard the end of their bar is almost scraping the dirt? Impressive. To begin with, shift your weight forward just like you normally would. However, this time you’re trying to coil a spring and generate inertia that can be unleashed on the exit.

To do this push into the berm harder than before and as you reach the mid-point or where the berm starts to leave you, push the bike away, like

you’re trying to do a strange manual whilst in the turn. If you get the timing right, this quick shift in weight will give you a burst of acceleration that you

will have never had before. It’s one of these things that you’ll know when you get it right.

This post was taken from: Mountain Biking The Manual by Chris Ball